Towards an attention-oriented view and an open basic attitude

About the relationship between imagination and our fight- and flight behaviour

Preface

In the book Sapiens, Yuval Noah Harari describes the history of man. I would like to recommend everyone to read that book and also its sequel, Homo Deus, to gain an insight into human and social development, from prehistoric times to the present, including the important challenges that we face in our present time. I will not give a comprehensive summary of the books but limit myself to the observation that the history of mankind is a special combination of circumstances with undesirable side effects.

The common thread in human history is a special quality: imagination. Harari refers to it in various ways. Humans can imagine something; have an idea, independent of reality. We developed material tools with which we could physically intervene in the world, such as axes and plows, and non-material tools such as language with words, rules and stories that allowed us to live together in large groups.

Over time, creating from our imagination has taken an enormous flight. Material and non-material tools have become increasingly complex and control more and more our way of living. Imagination thus puts an ever-greater stamp on our lives and because we are with an ever- increasing number of people, that intervene more and more in the world, the pressure on our environment becomes greater and greater. I don't think Homo sapiens is the only species with imagination or language on this planet, but I think what we do with it can be called unique. And that applies both in a constructive and in a destructive sense. I think it is safe to say that both what we have achieved over time and the major challenges we face in terms of living together, health and the environment, are directly related to the way homo sapiens has used his imagination. Imagination has brought us to where we are now. The question is whether imagination is suitable for solving the problems we have created with it?

I see imagination as the ability to make a representation of something. As humans, we use this ability to give meaning to what we perceive and what we do. Imagination includes all your assumptions, judgments and expectations. There are so many that you are only aware of a fraction. I don't think you're born with imagination. A newborn baby has no imagination yet.

At the end of this article I will answer that question, but I want to start with another question that I missed in the books Harari wrote, namely: in what way is imagination activated? In other words: what makes imagination possible?

I find the answer to that question when I think of what I need to be able to imagine. What I need is attention, and a special form of attention that I call focus-attention. (The reason why I call it that way, I will come back to later.) Focus-attention is needed for imagination and when we see what we can do with our imagination, I dare to state that Homo sapiens is world champion focussing.

Another question I then would like to ask is: where do the destructive effects of imagination come from? Why do we often think that following rules is more important than the well being of people and animals? How come we can kill in the name of a faith? Is man naturally bad? I do not think so. I think there is a biological reason. If we look at how we as humans work, it appears that focus- attention not only directs our imagination, but also our protection mechanism. Both are directed by alertness and paying attention. This means that the more we use imagination, the more we use a form of fighting, fleeing and freezing in our behaviour. The direct consequence of this is that people easily go into fight mode if they think their beliefs are under attack.

In this article I want to give an attention-oriented view to provides more insight into the relationship between attention, imagination and our fight, flight and freeze behaviour. After we have considered the social translation of these relationships, I want to delve deeper into the destructive side effects and end the article with the way in which I think we can limit these side effects.

In the past 20 years, in my work in foster care and aikido, I have researched what attention, and lack of attention, does to people and how we can influence and steer with our attention. This article links this lived through perspective to knowledge about our protection mechanism.

1 Seeing humans as an attention-being

As simple as it is to experience attention, it is all the more difficult to describe it. The descriptions that I have found range from awareness, through a cognitive process of perception to consciousness. (See my first article on attention for more background on this.) As far as I'm concerned, attention is connected to all three and to many more. I see attention as the basis, or better said, the condition for interest, perception, awareness, thinking and to come into action. Attention creates connections; it makes something possible. Without attention there would be no interest, awareness, perception, or targeted action. You would not be able to orientate, enjoy, investigate, or learn. Through attention we relate to the world in which we live. Viewed over time, this means that the way in which and what people have been paying attention to forms the basis for human development and civilization up to now. It also means that the way in which and what we will be paying attention to will determine our further development.

By the way, I don't want to claim that attention is exclusively a human thing. I also see animals and plants, just like humans, as attention beings, with often special attention-related traits that can differ enormously from those of humans. Consider the sense of direction of the carrier pigeon and the sense of smell of a dog; all attention related.

Seeing people as an attention being, living in this world together with other attention beings, is step one towards an attention-oriented view. Not only does it give a nice entrance to look at the relationship between people, animals and plants, but it also makes us realize that our lives are driven by attention. Many people think of advertising and social media if we talk about focusing attention, but as far as I'm concerned focussing attention is much broader. All language, music and other art expressions, all images, websites, game forms and journalism are all about focussing attention, just like all forms of education, politics, therapy and upbringing. And the work that you and your colleagues do is probably nothing then focusing attention; maybe you are directing your own attention and/or that of others. If you are not paying attention, then you might as well go home.

2 Two types of attention

Did you ever dwell on the sensation that someone who is angry seems to be a completely different person than the same person when he or she is acting nice and well-connected? I think that has everything to do with attention. If someone is angry, his or her attention is high. If someone is nice and well-connected, his or her attention is low. You could say that we use different types of attention. I name this as broad attention and focus-attention.

Step two towards an attention-oriented view is to realize that people can use two different types of attention. Both of them have their own functionality and are accompanied by a different kind of presence and physiology. This physiology has everything to do with our protection mechanism. Depending on the way you use your attention, you look at the world in a different way and have a different social interaction. So it is not only important what gets attention, but especially how something gets attention. It makes a difference whether someone, or something gets broad attention or focus-attention. To better understand the difference between the two types of attention, I want to take you to the basic principles of our attention system.

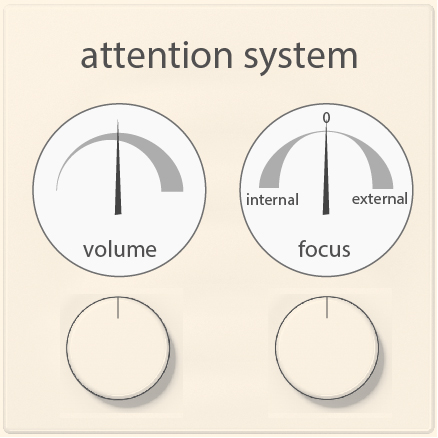

The basis of our attention system is ancient and has to do with the way in which we are connected to the world around us. It has only two essential variables. That is the extent of openness and the magnitude of filtering. The extent of openness determines whether you have much or little attention. If you are very open, there is a lot of connection, if you are more closed, then you have less connection. It is like a volume knob for the quantity of connection. The second variable, filtering, allows you to focus your attention. You can give more attention to one thing than the other. Translated into meters and rotary knobs, or dials, you could imagine it as in the figure shown.

The fact that there are dials could give you the idea that you have a lot of control over your attention. That is only partly true. Everything that attracts your attention is twisting your dials.

Broad attention

If there is openness and little or no filtering, then there is broad attention. Broad attention gives us an open, relaxed attitude and posture. We are healthy alert and use little energy. (Think of a man sitting on a bench and not doing anything, or better yet: think of a cow in the meadow.) Through broad attention we are connected to the world around us and because we derive our stability from this connection, you could say that broad attention is responsible for our stability. In daily life we use broad attention to make proper contact, to feel connected, to listen to someone and feel compassion. Broad attention brings acceptance, overview and tranquillity. In the broad attention we have no judgments and are not focused. We have broad attention from our centre. You automatically go to your broad attention when you relax, without sinking in, or when you connect from your centre.

Focus-attention

We use focus-attention if something narrows our attention. That may be a need (for example, eating, drinking, or social interaction), or imagination (for example, the idea that you have to do something, or a judgment that you have), or both. If attention narrows, it becomes goal-oriented, where the more important someone finds the goal, the greater the focus will be. Focus-attention is located high in the body. It influences our breathing, which becomes shorter, it makes us aware, activates our body, our protection mechanism and, as I earlier said, also our imagination. We are, as it were, in our head. We use focus-attention when we investigate something, when want to achieve, prevent or plan something and when we think.

The more you focus, the more focus-attention will influence your attitude, posture and behaviour. What that attitude and behaviour looks like depends on many factors, including the direction of the focus. This is because the focus can be directed outwards or inwards (see also the image). If our focus-attention is directed outside, our energy and power is also directed outside, into the world. In that state we are active on the outside, sometimes moving mountains and, if necessary, willing to fight (or flee) to get what we need. If the focus-attention is directed inwards, we become silent and we close: we freeze. We want to prevent ourself from making contact. The effort is, as it were, on the closure. We feel less pain in this state. This attitude can therefore be used as protection in situations in which we feel powerless and there is no point in fighting, or fleeing. A lot of attention is needed to close off properly, although this effort is not clearly visible on the outside. When a strong focus position becomes stuck in our system, and continues after the threat is gone, we speak of a trauma. We continue to fight, flee, or freeze even though that is no longer necessary. A trauma can therefore have serious social and physical consequences.

Although some people find it difficult, for most people the difference between broad attention, outward focus-attention and inward focus-attention can be felt physically well. Try it out. Sit back and enjoy the broad attention. Then focus for a while on something in the room and then go with your attention inside, into your body. Can you feel how your body reacts to these different forms of attention?

3 From broad attention to focus-attention as the most important attention

Step three towards an attention-oriented view is to realize that our modern way of life, literally, requires a different attention than a natural way of life.

In nature, broad attention is the natural starting point, the foundation for life. In nature: you are at rest unless you have to do something. In principle, animals only do what is necessary and do not use more energy than needed. That is only logical, because in nature energy is in principle scarce.

In our culture it works completely differently. Instead of what is needed, we often do what is possible. The adage often is: you are active unless you need rest.

Of course every generalisation about life is unqualified, but in a general sense you can say that broad attention is no longer the foundation of modern life. That place has been taken by focus-attention. The main reason for this is that imagination, in the form of goals, rules, expectations and assumptions, has become the basis on which we build our lives. We wake up and start imagining and we do not stop until we sleep. We imagine at work and we imagine at home. Even the moments that we do nothing are often filled with imagination. We use imagination and focus-attention throughout the day to keep track of our goals, expectations and assumptions. Little by little we experience the moments that we ourselves have broad attention, or receive it from someone else, as special moments.

So we spend most of our time in the focus-attention, which, as I mentioned earlier, is also connected to our protection system. But we are not fighting, flying, or freezing all day, are we? So, how does that work?

4 Focus-attention in a social context

Step four to an attention-oriented view is learning to see how we use the ways we naturally use to protect ourselves, now use it in a normal, nonthreatening, social context. In the course of time we have learned to translate our fight, flight and freeze attitude into social behaviour.

For example, if you see someone doing his best for something, you could say that he uses his fighting attitude for that, because there is focus-attention and effort. That fighting attitude can be very small, but will become clearer as the goal becomes more important and the stakes increase. Effort and focus can also point to a flight attitude. Fighting and fleeing are not easy to distinguish in a social context. Both are active and goal-oriented and they can also emerge. If someone devotes himself to his work, he does his utmost (fighting attitude), but it may well be that he does this, because he would rather not pay attention to something else (fleeing attitude).

The freeze attitude, with attention focused inwards, has many social variations. We take me-time, look away, or pretend it doesn't affect us. This attitude varies in daily life from ‘doing nothing’ to ‘feeling nothing’. We use this attitude more often than we realize. For example, we look away and restrain ourselves when we are confronted with antisocial behaviour, social injustice, animal suffering, or environmental problems that are too big for us to handle.

Much of our behaviour is a derivative of fighting, fleeing, and freezing, or a combination of these three. Combinations can become very complicated. Resistance, for example, is a combination of fighting and freezing and containing yourself is a combination of fleeing and freezing. In both cases we do our best not to connect. It gets more complicated when we resist to contain ourselves. It becomes less and less clear what it is that we are doing our best for.

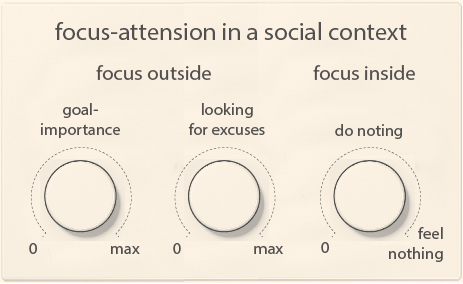

A life that is lived in focus-attention requires a new model. If we convert the social translation of fighting, fleeing and freezing into three rotary knobs, or dials, we get one dial for our goals, one for our excuses and one with which we can rest and turn off our feelings in an emergency. I simply call this the three-dial model.

We use this system in addition to the natural model that I described earlier, which has two dials. Broad attention forms the basis of this model. The more you live from focus-attention, the more the natural model is, as it were, overwritten by the three-button model, and the more this is the case, the more life feels like survival. The ways in which the two ways of living are interconnected is different from person to person.

Living from focus-attention is quite complicated and not everyone is equally skilled in it. We regularly make ‘mistakes’ and are confused. For example, we have a short fuse, feel rejected, or dare not respond, even though that would be healthy. I think that many of the misunderstandings and conflicts between people, but also many psychological problems and disorders, can be understood from this three-dial model.

5 Side effects of focus-attention and imagination

With the dominant role that focus-attention has in modern life, I think we can explain much of human behaviour that is so typical in modern times. It feels only logical that people are in their heads so much and it is understandable that there are so many conflicts between people. They are side effects of imagination and focus-attention. Step 5 towards an attention-oriented view is gaining insight into the limitations and destructive side effects of focus-attention and imagination on a large scale. I give some examples of both.

Less broad attention

Living with a lot of focus-attention means that we have less broad attention. All three dials must be turned off for broad attention. That means: not setting goals, not looking for excuses, not looking away and not feeling nothing. It also means making your own ideas less important and toning down your ego. For many people that sounds like a big task. It is therefore no longer evident for many people to have broad attention. And when we then realize what we need broad attention for, it becomes clear what sacrifice we have made with our modern way of living. Many people today find it genuinely difficult to feel connected and have great difficulties staying in balance. The result is suffering in all shapes and sizes. From neighbours fighting with each other to burnout, from depression to divorce.

Goal- and performance-oriented

Focus-attention makes us goal-oriented and performance-oriented. We use our fight- and flight mode in a safe environment. We have goals in all shapes and sizes; from large to small, from work to home and just about everything we do can be seen as an achievement. From eating healthy, being on time on an appointment, to meeting a deadline. This does not have to be a problem. It becomes a problem when our imagination makes us think our goals are really important and we base our self-image on our performance, because then we experience the failure to achieve our goals as a major setback, as if something bad happens to us, as if we have lost. For example, someone who comes second in a sports tournament can be really disappointed, because he did not win. This way we create a lot of tension and stress in our bodies and can easily lose the connection with other people, because goal-oriented work entails a tunnel vision. Both stress and poor connections make life tough. Something that you achieve as a group can also create tension and feelings of loss, maybe not in your own group, but in the opposing group. In addition to stress, performance-oriented thinking also creates inequality. I will elaborate on that right away.

Working in a goal- and performance-oriented way, without being based on a basic need, is not natural. We have to learn it. We therefore teach children from a young age to perform and to achieve goals. If you have no goals and you only do what is necessary to live a healthy life, your natural state, people will quickly find that a problem and nobody wants to be a problem. Living is not an achievement, but looking at life as the sum of achievements is the social norm. It is compelling and creates a lot of stress.

Tension and stress

Perhaps the most obvious side effect of focus-attention is the physical tension and stress that comes with it. It is perfectly logical this is the case, and it can be explained physically if you realize that focus-attention drives our protection mechanism. Many of the social problems that we struggle with are stress-related. A quick search on the Internet yields a huge list. Here is a short version: listlessness, eating problems, headache, muscle aches, sleep disorders, high blood pressure, dizziness, irritability, cynicism, concentration problems, uncertainty, hostility, dissatisfaction, anxiety, low self-esteem. Too much stress can lead to cardiovascular diseases, infectious diseases and disorders of muscles and joints, more use of coffee, alcohol, cigarettes and medication, with all the side effects that go with it. The result of all this is not only physical discomfort and illnesses, but also social tensions such as bullying, loneliness, neighbourhood disputes, depression, broken families and hostility between groups of people.

Given the physical and social destructive effects of stress, it seems to me of great importance that the relationship between focus-attention and diseases and disorders be further investigated. As far as I know that does not happen yet. Please let me know if I am wrong.

Inequality

Focus-attention creates a me-and-you feeling. Through our social loyalty and interdependence, this is increased in a society to a sense of us and them, and through imagination this is translated into a belief in inequality. Inequality means that one (kind of) person is worth more, is better than, the other (kind of) person. This is always imagination. This belief is destructive, because it creates conflicts in all shapes and sizes. History shows us horrible examples of this. Consider, for example, the persecution of the Jews and our slavery past. Both were only possible from imagination based on inequality. This kind of basic imagination still exists and expresses itself in many ways and areas. I am thinking, for example, of the inequality between men and women, between people with and without money, and between high and low educated people. I could also have given other examples. The only thing I want to make clear is that the belief in inequality is alive and kicking.

To summarise: a limited broad attention, belief in inequality, goal- and performance orientation and a lot of stress because of the dominant focus-attention is a cocktail that aggravates the lives of many people and is catastrophic for much of the rest of life on earth. If we look around us this becomes painfully clear. Animals are sacrificed daily, millions at a time, and I hardly know anyone who does not have anything to do with hurtful connections, insecurity, fatigue and/or physical limitations that aggravate life and unfortunately I am not alone in that observation.

What change is needed?

6 Towards an open basic attitude

What I think is needed is a change of attitude, with more emphasis on broad attention and less on focus-attention. That will diminish our belief in inequality and make goals and achievements less important. We will increasingly realize that problems that are the result of too much focus-attention cannot be solved with even more focus-attention. Fewer conflicts, more equality and an increasing sense of belonging will lower people's overall stress levels. We will become healthier and dare to trust each other more. People will choose less for self-interest and more for the common interest and we will see that nobody is guilty of the problems we encounter. So we don't have to fight anyone. It evolved like this because our imagination has unexpected side effects that we as a society do not yet understand so well and cannot yet regulate very good. It was and is ‘a special combination of circumstances with undesirable side effects’. We will see that we can also learn in this. Not our imagination, but our connections will be central.

What can we do to reduce the power of imagination? I think that is best done by taking imagination a little less seriously: it is just imagination. And it's our imagination. If we let our lives be controlled by something that we have made ourselves, then we are doing something wrong. Taking imagination less seriously, giving it less power, will not be easy for many people, because taking imagination less seriously means not only taking our delusions less seriously, but also our values, rules, assumptions and the image of ourselves, including our desires. How are we going to do that?

The best way to take our imagination a little less seriously is to take our connections more seriously and that is exactly what happens when we make our broad attention more important than our focus. By going to our broad attention, we create distance to the imagination. Connections, on the other hand, appear more prominently, not as a goal, but as a given. Because connections exist, you don't have to make an effort for that. In my lessons and courses I call this open attitude, in which connections play the first and imagination the second violin, ‘the basic attitude’.

An open basic attitude means that you have a good understanding of the situation, but are not too much inside your head. You are relaxed and can take action without giving up this relaxation. You coordinate in a way that fits the desired connection. What we need to unlearn is our natural reflex to fight, flight, or freeze whenever we feel unsafe and our cultural reflex that we must always do our best if we want to achieve something.

An open basic attitude is not an unattainable ideal. We already do it. Everything that you do very easily, without effort, but with nice attention, is done in the basic attitude. This can vary from taking a cup from the cupboard to performing complex actions in which you have mastered yourself. At those moments we use the two forms of attention at the same time and feel no distinction. We do it as a whole. This does not create inequality, not me-and-you.

The idea of acting as a whole can be found in many holistic beliefs, martial arts and disciplines that promote health such as yoga, qigong, tai chi and mindfulness. The open basic attitude, which you could also call 'mastery of attention', that sounds a bit more interesting, is therefore not new, I am aware of that. For me, foster care and aikido were the sources of inspiration for these insights.

Not new, but a new way of putting it into words, and an approach that explains many of the problems we are struggling with today and that also provides tools for finding a healthier balance. This theory is now supported by many exercises that I have developed in recent years, in which the relationship between people is the central theme. I like to share these exercises with everyone who is interested. I do this through personal coaching, workshops, courses and aikido lessons. Living from the basic attitude is living from the power of connection.

In my next article about attention I want to look at practical applications of the attention-oriented view and the open basic attitude and the relationship between attention and identity.

Thank you for reading this article. I invite you to share this article and I would appreciate it, if you leave a comment.

Hans de Win